Clean Code with YAGNI, KISS, SRP, SoC and IOSP, an Example (h4-10)

From the very beginning, you can write code that is easy to understand and easy to extent. Even beginners can try to follow some principles right from the start: You aren’t gonna need it (YAGNI), keep it simple, stupid (KISS), separation of concerns (SoC), single responsibility (SRP) and integration operation segregation (IOSP).

I’ll start here again with a quote from the book “Clean Code. A Handbook of Agile Software Craftsmanship” by Robert C. Martin:

Your code must be readable by other programmers. This is not simply a matter of writing nice comments. Rather, it requires that you craft the code in such a way that it reveals your intent.

This “other programmer” can also be yourself if you try to understand your own program that you wrote some time ago.

I have already described two tips for readable code in an earlier article: Follow coding conventions and don’t repeat your self (DRY). Now there are more to follow. I will explain this using the small program from the previous article.

YAGNI

In this series of articles, we are developing a game. The game is far from finished. We are currently developing the code for drawing the game board. In the last article, we wrote a method for coloring the shapes on the game board. This looks nice, but we don’t need it at the moment. The main thing is to have a functioning game in the first place. The colors are nice, maybe we could use them in the future, but right now it’s just holding us up. That’s why we’re leaving it out. We’re applying the YAGNI principle, YAGNI stands for “You aren’t gonna need it.” According to Wikipedia, Ron Jeffries once described it like this:

Always implement things when you actually need them, never when you just foresee that you need them.

KISS

Another principle is the KISS principle, which stands for “Keep it simple, stupid” or “Keep it simple and stupid”. This principle demands that you keep the code you write as simple as possible. The code from the last article actually follows this principle quite well, it is fairly straightforward and uncomplicated.

In the following steps, we will first change the code so that it still does exactly the same thing, but is structured differently. This makes it more complicated and less “simple and stupid”. So we are moving away a little from the KISS principle here. This is only OK here because our program is still in its infancy and we need a different structure for the subsequent extensions.

SoC

The abbreviation SoC stands for the separation of concerns principle. Wikipedia describes this principle as follows:

In computer science separation of concerns is a design principle for separating a computer program into distinct sections. Each section addresses a separate concern, a set of information that affects the code of a computer program.

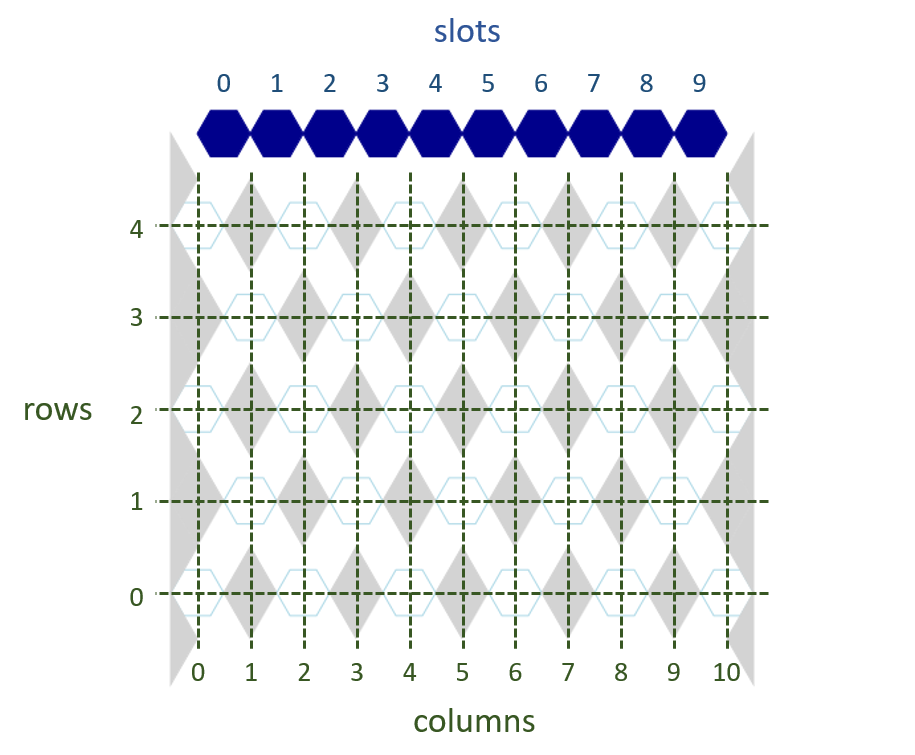

In order to understand what is meant by this, it is necessary to clarify what is meant by the term “concern”. In my view, a “concern” is something that is more fundamental. As an example, I take this picture from the article about the HexaFour game concept:

Two concerns of the game are presented here:

- On the one hand, the game has a user interface that the user can see. In this world, there are blue, hexagonal tiles and a game board with gray, rhomboid borders. And it is important that the blue pieces are exactly the right size to fit between the gray rhombuses.

- On the other hand, there is the logic of the game. The shape, color and size of the tiles are irrelevant here. The game board can be reduced to a grid of columns and rows. And the game pieces can move from one grid point to another according to certain rules.

These are two different concerns, user interface and logic, which we should separate as well as possible according to the SoC principle.

SRP

SRP stands for the single responsibility principle. Wikipedia explains this principle with three different descriptions:

A module should be responsible to one, and only one, actor […]

A class should have only one reason to change […]

Gather together the things that change for the same reasons. Separate those things that change for different reasons. […]

There is also an article The Single Responsibility Principle, in which Robert C. Martin, the originator of the term, describes what he means by it. In this article, Robert C. Martin speaks not only of “responsibilities”, but also of “concerns”. And the example he uses to explain the single responsibility principle could just as well be an explanation of the separation of concerns principle.

So what is the difference between the “official” definitions of SoC and SRP? I don’t know. In my interpretation, SoC is more about the bigger picture and SRP is more about aspects at the next level of detail. For SRP, this explanation helps me the most:

Separate those things that change for different reasons.

IOSP

SoC and SRP are about separating different things, concerns on the one hand and responsibilities on the other. How far can you take such a separation? The abbreviation IOSP stands for integration operation segregation principle. According to this principle, code consists of logic and integration, and these two things should also be separated as well as possible. If you do this consistently, there are two types of methods:

- Operation methods. This type of method should only contain logic, but not call any other methods of your code.

- Integration methods. This type of method should not contain any logic and only call other methods of your code.

A definition by Ralf Westphal sums it up like this:

Functions shall either only contain logic or they shall only call other functions.

There are many ways

Before we try to structure the first part of our HexaFour game according to the above principles, I would like to point out one thing: We will never manage to strictly follow all principles at all times. These are all just guidelines to help us write good code. Sometimes some do not fit the current problem, sometimes they even contradict each other. For example, if you strictly follow the single responsibility principle, the code can become more complicated and move away from the KISS principle.

To a certain extent, what you consider to be clean code also depends on your own preferences and strengths. On the web page Design-Types, for example, sixteen different types of developers are described. You can answer a questionnaire there and it will determine which design type you are. My design type, for example, is “The Engineer”. As this type, I don’t like the KISS principle as much as other principles. There are other types, for example “The Craftsman”, who like the KISS principle much more. There is no right and wrong. You have to find your own way. It’s also worth paying attention to the principles you don’t like. Because that’s where you might have a blind spot.

Application of the principles to the HexaFour example

We now apply the above principles to the HexaFour example from the previous post, and refactor the code.

Main method is an integration method

We rewrite the program a little bit:

internal class Program

{

public static void WoopecMain()

{

Configuration configuration = GetConfiguration();

InitializeTheGame(configuration);

PlayTheGame(configuration);

}

#region Configuration

// to be defined

#endregion Configuration

#region Initialization

// to be defined

#endregion Initialization

#region Play

// to be defined

#endregion Play

#region UserInterface

// to be defined

#endregion UserInterface

}

The program now essentially consists of four responsibilities: configuration, initialization, playing the actual game and the user interface. We want to keep the methods of different responsibilities well separated. To do this, we are using C# regions for the time being. This is only an interim solution. We should actually define separate classes for these different responsibilities. But we don’t know how to do that yet, so we’ll do it this way for now.

The main method is now a pure integration method, it contains no logic. It is therefore self-explanatory.

In the following, we will look at the code for the various responsibilities.

Configuration

We summarize all configuration properties in a record, and a method defines the current values:

private record Configuration(double TokenRadius, int MaxRow, int MaxColumn);

private static Configuration GetConfiguration()

{

return new Configuration(20.0, 4, 10);

}

The configuration could also be read from a file, or the user could enter it freely. But for now, the above solution is enough for us (YAGNI).

Game initialization

The entry point for game initialization is the InitializeTheGame method:

private static void InitializeTheGame(Configuration configuration)

{

var boardElements = new List<BoardElement>();

boardElements.AddRange(CreateRegularBoardElements(configuration.MaxRow, configuration.MaxColumn));

boardElements.AddRange(CreateBorderBoardElements(configuration.MaxRow, configuration.MaxColumn));

InitializeUserInterface(configuration, boardElements);

}

As mentioned above, there are two different concerns: game logic and user interface. We want to separate these as far as possible. The record BoardElement is part of the game logic:

private record BoardElement(string Shape, Color FillColor, double Row, double Column);

The following two methods create these board elements:

private static List<BoardElement> CreateRegularBoardElements(int maxRow, int maxColumn)

{

// Analogous to CreateGameBoard method from previous post

}

private static List<BoardElement> CreateBorderBoardElements(int maxRow, int maxColumn)

{

List<BoardElement> boardElements = new();

for (var row = -0.5; row <= maxRow + 0.5; row++)

{

boardElements.Add(new BoardElement("leftborder", Colors.LightGray, row, -0.5));

boardElements.Add(new BoardElement("rightborder", Colors.LightGray, row, maxColumn + 0.5));

}

return boardElements;

}

These are operations methods. So there is logic here. I won’t explain the methods in detail here because I have already done so in previous posts.

The generated BoardElements are passed on to the InitializeUserInterface method, which displays the elements on the screen.

User Interface

This method is the entry point to the user interface concern:

private static void InitializeUserInterface(Configuration configuration, List<BoardElement> boardElements)

{

RegisterRhombusShape(configuration.TokenRadius);

RegisterLeftBorderShape(configuration.TokenRadius);

RegisterRightBorderShape(configuration.TokenRadius);

RegisterTokenShape(configuration.TokenRadius);

DrawBoardElements(boardElements, configuration.TokenRadius);

}

This method receives all board elements created by the game logic and draws them on the screen.

To do this, it must first register different types of shapes under a name. For example like this:

public static void RegisterRhombusShape(double radius)

{

// See code in previous post

Shapes.Add("rhombus", polygon);

}

These two methods draw the elements on the screen:

private static void DrawBoardElements(List<BoardElement> boardElements, double radius)

{

foreach (var boardElement in boardElements)

{

DrawBoardElement(boardElement, radius);

}

}

private static void DrawBoardElement(BoardElement boardElement, double radius)

{

var figure = new Figure()

{

Shape = Shapes.Get(boardElement.Shape),

Color = boardElement.FillColor

};

// And so on, see code at the end of the previous post

}

This method is also part of the user interface:

private static UserInput AskUserForNextSlot(int maxCol)

{

int maxSlot = maxCol - 1;

int? numInput = Screen.Default.NumInput("Choose slot", $"Enter a slot-number in the range 0..{maxSlot}", maxSlot / 2, 0, maxSlot);

if (numInput == null)

return new UserInput(true, 0);

else

return new UserInput(false, numInput.GetValueOrDefault());

}

As a result, the method returns in a record which action the user would like to perform next:

private record UserInput(bool CancelGame, int Slot);

The game itself

All that’s missing now is the game itself.

The entry into game logic looks like this for now:

private static void PlayTheGame(Configuration configuration)

{

while (true)

{

UserInput userInput = AskUserForNextSlot(configuration.MaxColumn);

if (userInput.CancelGame)

return;

else

MakeMove(userInput.Slot, configuration.TokenRadius, configuration.MaxRow);

}

}

According to the IOSP principle, this should actually be a pure integration method. But this is not the case because the method also contains logic. However, I haven’t managed to do any better. Nevertheless, it is still self-explanatory from my point of view.

And now it’s time for the game itself:

private static void MakeMove(int slot, double tokenRadius, int maxRow)

{

// Of course, a lot is still missing here.

// As a first step, we create a token and display it in the right place.

BoardElement boardElement = CreateTokenBoardElementForSlot(slot, maxRow);

DrawBoardElement(boardElement, tokenRadius);

}

private static BoardElement CreateTokenBoardElementForSlot(int slot, int maxRow)

{

var slotCol = slot + 0.5;

var slotRow = maxRow + 0.5;

return new BoardElement("token", Colors.DarkBlue, slotRow, slotCol);

}

Of course, a lot is still missing. But the beginnings have already been made: The MakeMove method is an integration method. This calls an operation method in which the game logic is implemented. There is currently only one, the CreateTokenBoardElementForSlot method. And at the end, everything is passed on to a UserInterface method (DrawBoardElement), which takes care of the user interface concern.

The bottom line

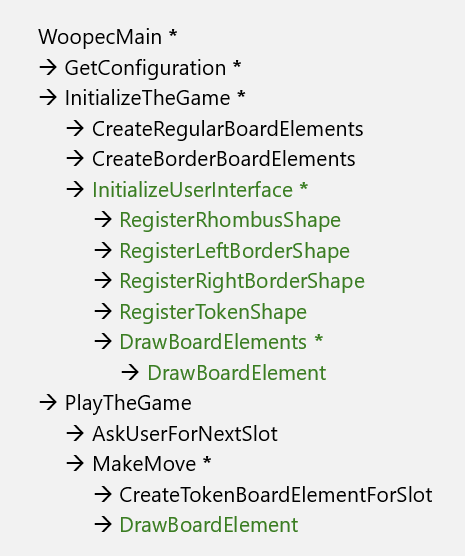

We can take a look at which methods are now available and how they call each other:

In this image, all integration methods are marked with an asterisk ( * ), all other methods are operation methods. You can see that we have followed the IOSP principle relatively well here, only the method PlayTheGame does not fit, because this method is an operation method and therefore should not call any other methods. But from my point of view, this structure is good enough.

All methods that deal with the user interface concern are highlighted in green. We have separated this concern well from the concern of game logic. The code therefore also follows the SoC principle

What’s the situation with SRP? The code is now divided into many methods and each method is only responsible for one thing. That should be good enough up to this point. But there is actually more to improve here, because all the code is in a single class. So this one class is responsible for all the different things. This does not fit with SRP. There should actually be more classes. But to do that, we first need to know how to define classes. I’ll do that in one of the next articles.

The code is growing and becoming too large to describe in full in an article, but you can find all the code on GitHub from now on. In the next post, I will describe a few basics about GitHub.

TL;DR

This post is part of a series. You can find the previous post here and an overview here.

Clean Code:

- YAGNI: Always implement things when you actually need them, never when you just foresee that you need them.

- KISS: Keep it simple, stupid.

- SoC: Separating the program into distinct sections. Each section addresses a separate concern.

- SRP: Separate those things that change for different reasons.

- IOSP: Functions shall either only contain logic or they shall only call other functions.

- Principles can conflict: You have to find your own way.

Comment on this post ❤️

I am very interested in what readers think of this post and what ideas or questions they have. The easiest way to do this is to respond to my anonymous survey.